Colonialism and Mexican revolution

Land and freedom 'Tierra y libertad'

Feudalism and the introduction of coffee to Mexico (1880-1900)

Coffee had been imported to Mexico as a colonial product in the 1880s using German capital among others. It was supposed to be produced exclusively for export. The Mexican state was expecting an economic upturn due to this foreign investment as the country was facing bankruptcy after the armed raid and land seizure by the US in the 1840s. During the 35 year-long dictatorship of president Porfirio Diaz, the so-called Porfiriate (1877 to 1911), Mexican real estate had been redistributed to the benefit of mestizos [1] and major landowners [2]: Land owned by Spanish colonial lords prior to Mexican independence and subsequently re-appropriated by indigenous communities was declared as 'no man's land' due to the lack of land titles. It was distributed as debt payment to public employees who thus had become major landowners and were frequently establishing coffee fincas. As a consequence, about 90% of the rural population lost their land and had to hire themselves out as slave labourers. In South Mexican Chiapas, home to the majority of today's Zapatistas, coffee enterprises doubled between 1890-1910.

Due to the establishment of fincas and major landowners, feudal relations like during Spanish colonialism were resurrected. Indigenous communities were not merely landless, but deprived of any rights and self-rule and therefore doomed to serve their landowners. Abuse and corporal punishment until death were the order of the day.

Social unrest and revolution (1900-1920)

Resistance based on several social strata began to stand up against the Porfiriate. Landless and indigenous people wanted their land back and break free of feudal relations. The middle class also distanced itself from Diaz because they were suffering from repercussions of the economic crisis prevailing in the US since 1907. Riches were distributed to the benefit of the upper class only.

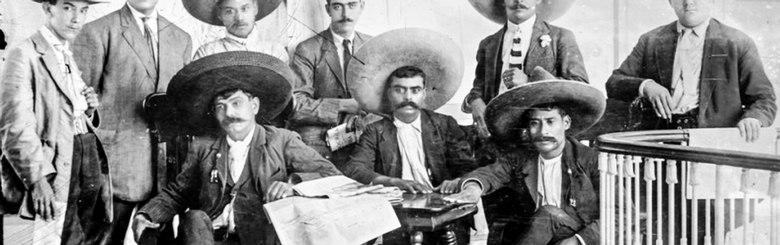

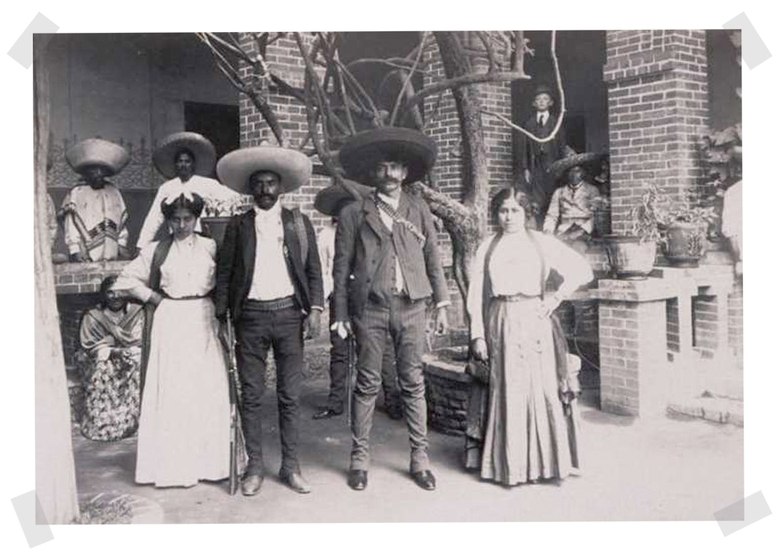

In 1910 Diaz was supposed to be re-elected as president staging a fraudulent election. A powerful opposition movement following Francisco Madero was contesting this with military means. Among the rebels was Emiliano Zapata with his army of landless rural workers from Mexico's Southern regions. After a successful rebellion spreading over the entire country, Diaz was forced to flee in 1911 and Madero was elected the new president. However, he disappointed the hopes of a renewal of the army, exchange of old public officials and land reform. Madero thus turned against his own ideals and former associates. Zapatistas fighting for 'Tierra y Libertad' (land and freedom) were therefore opposing him now as well. Finally, only two years after his election as president he was murdered in a military coup by Victoriano Huerta. Subsequently, Huerta was seizing power but was only able to maintain this position for one year. Zapata was murdered in 1919 and until 1920 the land was shaken by civil war.

Agricultural reform and institutionalisation (1920-1970)

Àlvaro Obregón was elected the new president in 1920 and during his office, the Mexican Revolution is supposed to have calmed down and political conditions consolidated. However, many demands and hopes of the people had not been fulfilled yet. Only Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940) managed to implement long-demanded reforms like nationalisation of the oil industry and the foreign-owned railway company. Additionally, he succeeded in rolling back the influence of still powerful major landowners in the provinces by implementing the agricultural reforms demanded by the Zapatistas.

But this hesitant land reform to the benefit of indigenous farmers was hardly implemented in the Chiapas region. Thus, between 1930 and 1980, 750 280 hectares were officially allocated to indigenous applicants but 'of these only 141 383 hectares were really transferred. Of these, one quarter had already been communities' land before and the remainder was mostly very poor soil.'[3]

Indigenous uprisings and self-organisation (1970-1984)

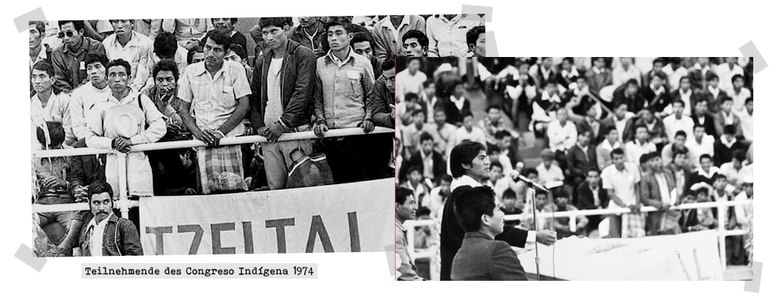

In the 1970s indigenous population began to organise themselves in farmers' organisations. Under the umbrella of the church, Congreso Indigena took place in 1974, the Chiapas indigenous movement's hour of birth. Indigenous people of all major ethnic groups were meeting and discussing their political situation and common problems. This meeting has been the kick-off for organised resistance and they were conquering all land between 1972 and 1983.

Important conditions for the success of self-organisation and empowerment have been:

- Major landowners had been converting to extensive stock farming promising higher profits than coffee cultivation. Additionally, more and more machinery was implemented to coffee production. Many workers lost their jobs due to these developments and were chased off the fincas.

- A public dam project for energy production was threatening thousands of hectares of land. However, only major landowners were compensated for their land. (In 1981 the project was cancelled due to the resistance, but it has been resurrected in the context of the Puebla-Panamá plan.)

- Increasing disgruntlement of the rural population was prevailing due to lack of real agricultural reforms and land re-distribution.

- Due to injustice and existential poverty, indigenous people were beginning to organise as farmers' movement. This self-organisation was supported by Marxist intellectuals radicalised in the students' movement in the 68s.

- Liberation theologists, Father Joél Patron of San Cristobal in particular, are regarded as champions of indigenous people's rights and were substantially supporting resistance.

The state was reacting repressively to the squatting of land despite the land being frequently in the official ownership of the farmers for quite some time! Subsequently, representatives from some 600 communities were coming to Mexico City in 1984 and succeeded not only in releasing political prisoners but also obtaining official entitlement to squatted land.

An atmosphere of change was prevailing: alphabetisation took place and farmers began collectively to establish new communities for the first time and to cultivate coffee for their own benefit.

Organisation and drawbacks (1980s to 1994)

Many farmers were organising in the Maoist farmers' organisation Unión de Uniones. Unión was quite successful and gave rise to a credit union. This allowed for the legal purchase of additional land. Coached by urban counsellors, some communities started to organise collectively in coffee cultivation. This experiment, however, failed due to resentment, envy and an idea of collectivisation not considering local conditions and traditions. This was aggravated by constantly fluctuating market prices, dependency on intermediaries and the free fall of the coffee price in 1989. Only the debts remained.

Additionally, Unión de Uniones, formerly in opposition to the state, changed into a propaganda tool for land privatisation. Thus, during the presidential election campaign, Unión speakers turned against indigenous farmers and attempted to privatise common land not for sale. The indigenous movement appeared devastated.

Zapatista uprising and new coffee cooperatives (1994 till today)

The coffee price crisis and the NAFTA agreement [4] abolishing import tax on US agricultural products and forcing small-scale farmers into direct competition with big US corporations threatened the existence of the indigenous population: 'With NAFTA, they will kill us without bullets.'[5]

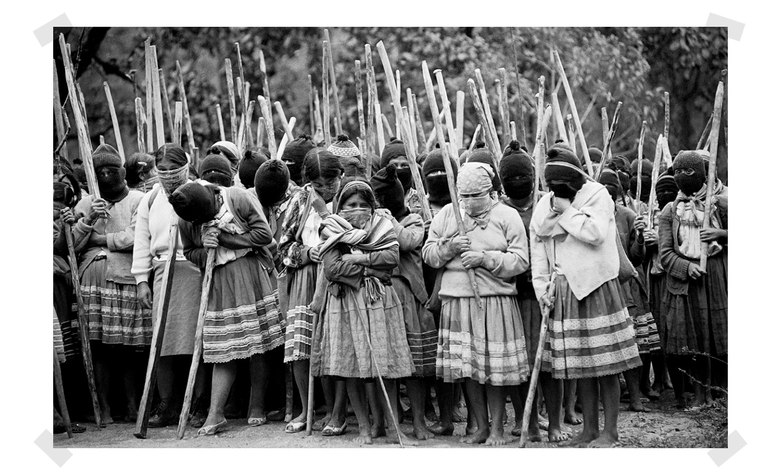

In their perception, there was only one way to break free of existence in poverty and marginalisation: armed rebellion. They organised as indigenous rebels, as Zapatistas, and squatted five regional capitals in Chiapas and declared war to the Mexican government on 01/01/1994, the effective date of the free trade agreement. (see also 'Who are the Zapatistas and how are they organising?').

Due to the pressure of civil society, armed struggles with the government were terminated after 12 days and two years later, indigenous people's autonomy rights were defined in the San Andrés agreement. However, subsequently the Mexican state refused to accept and implement these rights and used military force to fight the Zapatistas. Zapatistas, in turn, reacted by an international mobilisation for their rights and thereby inspiring the globalisation-critical left with significant impulses.

In 1996 visitors from all over the world were invited to the 'Inter-galactical Meeting Against Neo-liberalism and for Humankind'. The opening of communities for some 3000 visitors from 54 nations allowed for strong cooperation with supporters. Consequently, international practical solidarity instigated the establishment of Mut Vitz, the first Zapatista coffee cooperative producing for export. The coop's objective was to break the dependency on intermediaries by using contacts abroad to export their coffee directly. They have succeeded: finally, a fair coffee price was paid and the Zapatista movement in general benefited from support, including financial sponsoring, of their ambitions of autonomy.

Meanwhile, there are two big Zapatista coffee cooperatives with more than 1200 members exporting to eight countries. The coffee coops' success is contributing significantly to Zapatista economic autonomy and allows for independence of governmental programs or projects frequently serving as camouflage to generate new dependencies or to break autonomy ambitions.

[1] This term goes back to colonialism and describes descendants of Spanish and indigenous ancestors in Latin America. 'Mestizos' elevated themselves above indigenous people, enjoying more rights and privileges.

[2] http://www.deutschlandfunk.de/ende-eines-regimes.871.de.html?dram:article_id=127344 (03.02.2018)

[3] P. Gerber (2005): Das Aroma der Rebellion, p. 25.

[4] North American Free Trade Agreement

[5] Subcomandante Marcos in: Marta Durán de Huerta (1994/2001): Yo Marcos. Gespräche über die zapatistische Bewegung, p. 94