Fair trade under scrutiny

Limits of fair trade

Introduction: The jungle of labels

There are some 1000 labels in Germany which are supposed to reassure consumers that the products are 'sustainable' and produced 'fairly' or particularly environment-friendly. Labels are 'general description(s) for word or symbol markings on the products'[1], that are not necessarily legally monitored. It is not entirely clear what this praise is hiding because the terms 'fair' or 'sustainable' are not protected by law.

A good overview of requirements and implementations in the name of fair trade is provided by Ökotest (2012/8). This magazine reports, for instance, that producers of Chiquita bananas displaying a Rainforest Alliance Label neither receive a minimum price for their bananas nor prefinancing usually negotiated in the fair trade sector.[2]. Similarly, the 'Teegut' chain's organic bananas displaying the 'Fairbindet' label get prefinancing as well as a minimum price 'on principle' only.[3]. Equally unsatisfactory is the discovery that the additional money earned by the Edeka supermarket chain for their relatively expensive milk labelled 'Our home – act fairly' and '40 cent per litre for our milk farmers' has never been reimbursed to the farmers, according to Ökotest research.[4]. These examples could be continued. To sum up, the crucial problem is the lack of minimum requirements and certification standards for these type of self-labels, they have been created arbitrarily for the company's own products. Each brand can call itself whatever it wants and can sport a label of sustainability and fairness independent of their realisation. Obviously, profit margins of products are increasing if labelled.[5]

Yet, not every label is just a marketing gag. Several organic seals and fair trade labels possess definite standards and control mechanisms.

Fair trade labels and definitions

Most important and well-known labels are the World Fair Trade Organization label and the Fairtrade seal. Despite the organisations in question are travelling different paths regarding fair trade, they are referring to the same definition of fair trade and they are both organised in Forum Fairer Handel, e.g. for purposes of training and promotion of fair trade.

'Fair trade is a trade partnership based on dialogue, transparency and respect and in pursuit of more fairness in international trade. By establishing better trade conditions and safeguarding of social rights for disadvantaged producers and workers particularly in the countries of the South, fair trade is contributing to sustainable development. Fair trade organisations, along with consumers, are involved in support of producers, shaping of consciousness as well as campaign work to change rules and practices of conventional world trade.' [6]

While on first sight these organisations appear united, they are committed to quite different traditions and market mechanisms. A look back seems helpful.

Historical roots of fair trade

At the beginning of the seventies, protests against increasing injustice in world trade gave rise to church-based One- or Third-world shops. In several countries, small associations started to organise direct trade of food and its distribution in markets or church communities. Products like bananas or tea were purchased from cooperatives in the global South, based on personal contacts. Over the years, these contacts intensified. Know-how has been exchanged while visiting the coops, prices have been negotiated individually and long-term trade relations have been forged. Traders, working nearly without exception unpaid, strived via sales of products to illuminate exploitative trade relations with the global South and to radically change and finally abolish conventional trade.

At the end of the seventies, more and more internationalist solidarity political groups were joining the coffee trade. Nicaraguan coffee was sold in Germany for the first time in 1980 to support small-scale farmers fighting against the Somoza dictatorship (overthrown 1979). The so-called 'Sandino-Dröhnung' (completely hammered by Sandino), distributed by Gepa and Ökotopia among others, was consumed primarily for reasons of solidarity.

Subsequently, 'cooperative coffee not bigwig coffee' was distributed in Germany by coffee project Café Cortadora in the context of the El Salvadorian war.[7] These trade relations were focusing on a revolutionary perspective supposed to change society and on the question of how to support efficiently the resistance of groups that were poor, oppressed by dictatorships and fought by armed forces. The call to buy any particular coffee, therefore, was more often than not simultaneously supporting liberation movements and social protests. There was much more at stake than the design of trade relations, the objectives ranging from the creation of a worldwide network of political activists to the world revolution some activists were hoping for.

Thanks to the success of both the church-oriented as well as the political-revolutionary movement (which were not that easy to distinguish anyway), more and more consumers could be won over, world shops were becoming more widespread as political-revolutionary groups were also distributing their coffee via the world shops and local initiatives were uniting in networks. Alas, neither the hoped-for revolution did take place nor the establishment of fair international trade.

As socialist economic models were waning, neo-liberal globalisation has taken off on its triumphal course and global markets have become increasingly delimited. New regional conflicts and wars are aggravating global living conditions as drastically as the consequences of climate change and over-exploitative depletion of resources in increasingly remote areas. Even the last niches in rain forests, indigenous communities or urban spaces are developed and exploited.

Introduction of seals and new markets

After the collapse of the coffee agreement in 1989 coffee world market price plummeted during the nineties and producers were striving for new markets.[8] Consequently, GEPA has expanded its distribution of fairly traded products to supermarkets and health food shops as well as to wholesale and mail order businesses.

All over Europe seals were created on a national scale to facilitate sales beyond the limited market segment of world shops. Hence, in Germany TransFair e.V. has been established in 1992 implementing the TransFair seal.

Due to increasing globalisation and networking, national seal organisations of the global North have united establishing the umbrella organisation Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (FLO) headquartered in Bonn in 1997. Beneath this umbrella, an internationally recognisable standard fair trade seal has been created. At the same time, the establishment of seals in the nineties and the harmonisation of product standards have initiated the cooperation with conventional trade chains. 'Matters of education policy have been pushed to the background due to an increasing emphasis on economic aspects' as a common criticism went.[9]

Current developments and rising sales

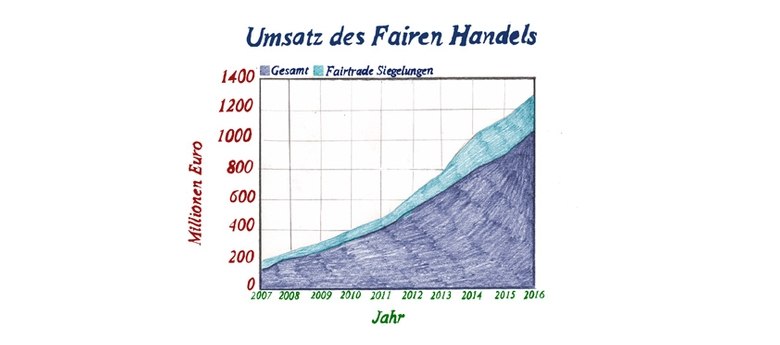

Cooperation with multinational chains has increased sales of fairly traded products every year. The manager of the TransFair e.V. Association has reported that sales of Fairtrade-sealed products have surpassed the billion mark for the first time in 2016.[10]

Quantitative success and the 'fair' products' entry into the mainstream is to a certain extent contributing to an increased consciousness on a societal level regarding unequal trade relations and to an expansion of sales markets for producers. However, this development comes at a price: 'Fair' products are displayed next to 'unfair' ones on the supermarket shelves. As a consequence, these products are not only subject to obvious price competition but, additionally, the 'position of the conventional market system has been justified.'[12] Adversarial development and radical questioning of conventional trade as in anti-locations like world shops realising trade relations characterised by cooperation have become moot by the very same products' inclusion into the supermarkets. The establishment of a radically different trade system has given way to the notion of individual freedom of decision to purchase any product.

Political responsibility for capitalist exploitation relations is individualised to a mere purchase decision, the entitlement to fair wages and a decent life is transferred into the commercial sphere of charity. Conditions of production beyond poverty and tyranny are transformed into a quality feature with its own price instead of being the irrevocable base of human relations.

Different approaches to fair trade – the establishment of an alternative trade structure vs. certification of individual products using conventional trade structures – are illustrated by the differences between fair trade labels.

The World Fair Trade Organization-Label (WFTO)

Standards and criteria are established by the World Fair Trade Organization headquartered in the Netherlands. It is the international umbrella organisation for more than 400 fair trade organisations in some 70 countries on all continents. At the same time, it is a global network of all participants of the value-added chain – from producers to consumers.[13]

Producer organisations, importers and world shops can be certified; therefore, companies, as well as products, are displaying the WFTO seal, for instance, El Puente and GEPA.[14]

Internal and external monitoring systems are in place reviewing the members regularly according to ten self-implemented principles devised collectively by experts from the global North and South. Self-assessment, exchange of expertise between colleagues and monitoring by external inspectors are parts of this process. [15] As a special feature, the organisation as a whole is reviewed and the seal is confirming the fairness of its entire business activity. [16] Thus, certification is focusing on the integrated trade chain (this is represented in the term 'Fair Trade' using two separate words.)

The 10 WFTO principles: 'WFTO members…

- * are creating opportunities for economically disadvantaged producers,

- * are applying transparency and responsibility to their business activity to the benefit of the producers,

- * are precluding maximisation of profits to the producers' detriment, respectively are committing themselves to prefinancing if desired, long term trade relations etc.,

- * are paying a fair price negotiated in dialogue and viewed as fair by the producers,

- * are forsaking forced labour and respecting UN conventions regarding children's rights,

- * are standing up for gender equality, non-discrimination and freedom of assembly,

- * are establishing healthy and safe working conditions,

- * are supporting vocational training of producers and of their own workforce,

- * are promoting fair trade and campaigning on a political level for more fairness in international trade,

- * are supporting measures of protection of resources and the environment'.[17]

We agree with the WFTO principles and, moreover, support the approach of focusing on the entire trade chain. For this reason, we are cooperating with e.g. El Puente and their products can be purchased via Café Libertad Kollektiv.

The Fairtrade seal

The international organisation Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (FLO [18]) is an association of 23 member organisations, three producer networks and 20 national Fairtrade organisations headquartered in Bonn.[19] The association is developing international fair trade standards incorporating 50% representation of votes of producer organisations.[20]. These standards cover the sectors 'social', 'ecologic' and 'economic issues' and are continually specified for small-scale farmers, plantation workers and individual products.[21]. Therefore, standards vary according to product.

Additionally, certification can not only be applied to the company's final products but also to single raw materials like sugar which are subsequently processed in a product line. In this case, the final product is displaying a program seal as opposed to a product seal.

Producers receive certification by meeting minimum requirements. Additionally, a development process for the next years is established including the objective of standard enhancement.

Fairtrade seal criteria are as follows:

- * payment of a break-even price and of an additional organic premium if applicable [currently 1,40$ per pound (almost 500g) + 0,30$ organic premium [22]],

- * payment of an additional Fairtrade premium for development measures [+ 0,20$],

- * provision of prefinancing,

- * long-term trade relations,

- * measures to ensure balancing of volumes and physical traceability [sales of Fairtrade products shouldn't surpass the availability of certified raw materials. Additionally, the delivery chain has to be retraceable. Thus, the certified product is supposed to end up at the consumers.],

- * physical traceability and possible annulment regarding cocoa, sugar, tea and fruit juice, [this is introducing the annulment of the aforementioned criterion: as cocoa, sugar, tea and juice are produced in big quantities, the mix or exchange of Fairtrade-certified and uncertified raw materials is expected]

- * 100 per cent rule and minimum requirements regarding mixed products [23] [every component of the product being possibly subject to fair production has to be obtained from fair production 'all that can be fair must be fair', water, for instance, being an exception.]

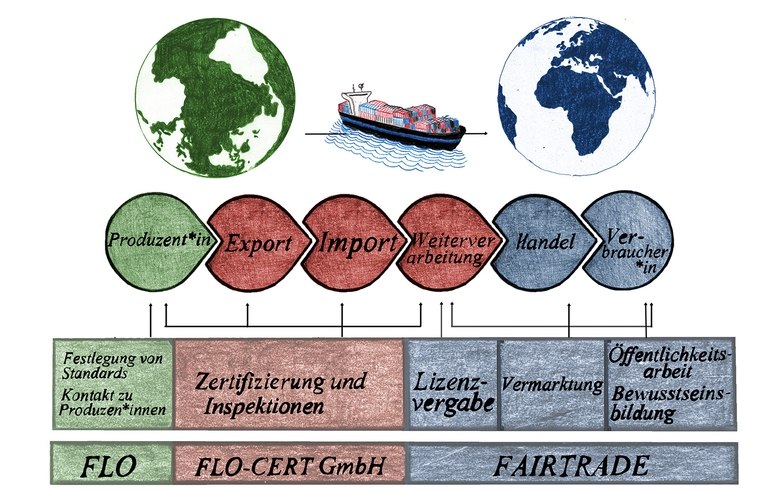

These standards are monitored by the independent certification company FLO-CERT GmbH. The review is taking place in announced and unannounced audits by local inspectors.

Certification costs have to be covered by producers as well as importers and exporters. If a company desires to sell products displaying a Fairtrade seal, it is subject to license fees by the national branch of FLO, TransFair e.V. in Germany. The sellers are exempt from control of their other trade practices and working conditions.

TransFair e.V. is representing Fairtrade in Germany and is dedicating itself to public relations, marketing, lobbying and campaigning besides selling the seal. The figure below is illustrating the division of tasks between the three players FLO, FLO-CERT and TransFair e.V.

Criticism

There are several points of criticism regarding the FLO-CERT seal. These are mentioned briefly as follows, to be elaborated in a more detailed way below:

1. Certification costs have to be covered by the farmers,

2. there is no purchase guarantee,

3. colonial continuities and greenwashing

4. weakening of seal standards for profit maximisation,

5. the lion's share of financial means remains in the global North.

1. Certification costs have to be covered by the farmers

Costs and bureaucratic obstacles of certification are quite high. If farmers intend to get certification, they have to pay a lump-sum application fee of € 500 independent of the certification process' result. This financial hurdle is ensuring the poorest farmers getting no certificate as they cannot afford to apply for better wages.

This, however, is just the beginning of producers' costs as farmers are obliged to pay certification fees for every kilo of coffee. An example: 60 small-scale farmers producing coffee individually so far intend to sell Fairtrade coffee collectively. They own six parcels of land being cultivated by three to six employees (29 in total, most of them family members). There are no additional sub-contractors. Coffee fees amount to € 4000 for the first year alone![25] Every additional year is subject to more fees. There is no way a really poor farmer family is able to buy themselves a 'fair price' and thereby the concept is biting its own tail. Consequently, more and more major landowners and plantation farmers are participating in Fairtrade. It is hardly surprising that many scientific studies are questioning the effect of Fairtrade on poverty reduction.[26]

2. No purchase guarantee

As outlined above, the producers' certification costs are massive. Additionally, there is no purchase guarantee for raw materials, only one third is traded fairly.[27] While long-term trade relations are promoted by FLO standards, producers are removed from consumers by the establishment of intermediaries. The company is buying from intermediate traders instead of contacting the producers directly. As a consequence, trade relations are loose, real long-term trade relations based on mutual exchange being rare. The intermediaries are the primary beneficiaries under these conditions.

Consequences of uncertain purchase quantities are twofold: On the one hand, a producer organisation having had their products certified for much money can't find an intermediary buying the goods for the premium price. Thereby the investment has been in vain which can result in the farmers' ruin.

On the other hand, producers' strategies tend to ensure life-supporting income by the selection of sold coffee's quality: qualitatively inferior coffee is fair-certified and sold to secure at least minimum wage while superior coffee is supplied on the free market fetching a better price. As this certainly makes sense from the producers' point of view, it is exerting a negative influence on Fairtrade quality.

3. Colonial continuities and greenwashing

As ethical criteria and control structures are established by protagonists from the global North and applied to producers of the global South, colonial continuities are reproduced: Rules are determined in the destination country of consumption and have to be followed in production countries. Producers have to comply with all given standards in order to realise cost-covering income. The problem of the focus on so-called 'underdeveloped countries' becomes obvious: Control personnel is supervising whether hard-working farmers do have an entitlement to break even – like the low wage problem is caused by the farmers!

At the same time, there aren't any fairness controls applied to global North companies distributing Fairtrade. Hence the Lidl supermarket chain finished second in the TransFair e.V. 'Fairtrade- Awards' in 2012 and in 2016 even managed to win the award. Lidl is one of the world's biggest discounters and detailed reports on abysmal working conditions can be found in the 'Lidl Black Book'. Furthermore, Lidl is widely criticised for its general pricing policy responsible for 'dwindling opportunities for rural agriculture in both the North and the South'.[28]

If particular products displaying the Fairtrade seal are introduced, their market image will be enhanced. In our opinion, TransFair e.V. is practising greenwashing by granting their award to Lidl – creating the image of a responsible company without any adequate basis thereof.[29]. This is opening the door for other multinational corporations and supermarket chains intending to polish their image by supplying 'fair' products; product labelling being a door-opener for sales is an open secret. As the company develops a small product line labelled to confirm e.g. fair working conditions, sales figures are increasing. Responsible consumers are purchasing the slightly more expensive labelled products and, consequently, the company's non-labelled products as well because trust in the brand as a whole has been enhanced. Finally, the brand's image has been improved, sales have increased and consumers have a clear conscience. Greenwashing is the term summing this up: the company cleaning itself, becoming ecologically and socially 'green', meaning pure, without fundamentally changing their exploitative practices.[30]

4. Weakening of seal standards for profit maximisation

- Minimum prices: When buying Fairtrade products, consumers assume that primarily producers will benefit from higher sales prices, Unfortunately, this is not the case: 1. FLO standard merely guarantees the payment of 'cost-covering' prices, thereby just ensuring the producers not suffering losses. The distinction as 'fair' appears almost cynical. 2. Not all products are subject to minimum prices, exemptions being e.g. raw cane sugar and spices. Justifications are provided as follows: 'The waiving of a Fairtrade minimum price is ultimately facilitating the participation in fair trade of as many farmers as possible and the introduction of additional products from various countries to Fairtrade certification'.[31] Put simply, this means there are more certifications if self-imposed standards are weakened. Consequently, more products are displaying the seal – but certainly not to the benefit of the producers!

- Mixed products: The required minimum proportion of fairly traded ingredients to acquire the seal was decreased from 50 to 20 per cent in July 2011. All other ingredients have to be fairly traded if available.[32]. If not for the decrease, several products would have been excluded from the system like drinks, ice cream or cookies. Forum Fairer Handel comments on this as follows: 'There is great interest in these products on part of suppliers and sellers. The 20% rule is based on FLO's goodwill to allow the development of these product lines and to open respective markets to producers.'[33]

- Balancing of volumes: Physical traceability doesn't apply to all products. Hence, the system in place is similar to green electricity: customers pay for green electricity but receive an energy mixture out of their sockets. In e.g. juice or chocolate production there is no guarantee of 100% of Fairtrade raw materials ending up in the final product; merely an assurance that not more Fairtrade final products will be sold than all fairly traded raw materials provided for production - for economic reasons. Worst case, there aren't any Fairtrade raw materials to be found in the certified Fairtrade chocolate.[34].

5. Financial means remain in the global North

As early as 2013, more than 5,5 billion euro had been spent on Fairtrade products.[35]. The boom is continuing, sales of certified products have already met the one billion euro mark. When reviewing the Fairtrade network in figure 3 above, the crucial role of FLO-CERT GmbH within the certification system becomes obvious. They are certifying producers, exporters and importers – and every single participant has to pay for their certificate. There is some suspicion that this enterprise is quite profitable due to the number of participants obliged to pay. Scrutiny of the company's legal form is supporting this suspicion: FLO-CERT is organised as a private limited company (GmbH) which as a corporate enterprise is not accountable to the public regarding debits and credits as for instance a non-profit association would be.

Some years ago, the internet was buzzing with rumours of FLO-CERT having realised profits of more than 10 million euro in 2014. Currently, there is no way, not even on request (!), of getting any information on sales or profits, let alone an annual financial statement. This is prompting speculations that the positive development of the Fairtrade market was also increasing FLO-CERT's profits enormously. Yet, the certification company's success story appears incompatible with Fairtrade marketing as it is giving rise to suspicion whether all the additional money spent by consumers is ending up with the producers instead of FLO-CERT's headquarters in Bonn.

There are additional hints on Fairtrade (like in traditional trade) realising the biggest proportion of sales in the products' target countries: 'Christiane Manthey, food expert of the consumer advice centre Baden-Württemberg, is referring to studies reporting that the biggest share of profits is remaining at manufacturers and trade chains instead of small-scale farmers and agricultural workers.'[36]

A substantial proportion of the premium on the fair products' sales price is therefore originating with marketing costs instead of harvest workers' higher wages or small-scale farmers' better raw coffee prices. Consumers' willingness to pay higher prices is thus promoting brand development, packaging and advertising industries in industrialised countries instead of communities and cooperatives' development in producer countries

Conclusion and positioning: Why Café Libertad Kollektiv is not using seals

Fair seals' standards are leaving much to be desired and considerable compromises have been made in order to remain competitive in both the market and the label jungle – to the producers' detriment. Additionally, a huge share of Fairtrade sales are realised in supermarkets - exactly the companies destroying local markets systematically via pricing policy.

While WTFO is at least maintaining a standard of politically advocating fairness in global trade, this is not the case with companies selling the Fairtrade seal. As a consequence, supermarket consumers do not obtain information (as is the usual educational and political standard e.g. in world shops) and more often than not aren't able to distinguish between the numerous labels and seals. Consequently, it seems irrelevant whether organic and fairly traded products are purchased in supermarkets or health food stores and world shops. Hence more and more small shops are giving up as they can't withstand the pressure of price competition with discounters.[37]. In our view, solidary coffee trade is incompatible with supermarket distribution channels.

Status quo of fair trade development suggests that in this sector, as elsewhere, capitalist market structures are prevailing and respective label and seal initiatives have to hold their own on the market. Some of them are in fact trying to meet the needs and requirements of producers, traders and consumers by putting forward different points of emphasis, but they shy away from a consistent break-up with players and mechanisms of global and local trade.

As described above, capitalist exploitation logic is penetrating and nobody can extricate themselves. This applies to fair trade as well – in spite of all attempts to withstand prevailing structures or to soften the direst consequences of e.g. price dumping.

Our criticism regarding certifications like the FLO-CERT seal notwithstanding, we perceive capitalist structures as the fundamental problem: global trade and market structures result in poverty. This could be tackled on the political level, e.g. general fixed minimum wages applied to import products and the legal exclusion of exploitative trade relations.

It is left to NGOs and initiatives instead to implement own standards they intend to follow. Subsequently, brands have to hold their own in the market and even to compete with each other, as can be observed in the label jungle. Competition with traditionally traded products on the one hand and labelled goods on the other is resulting in the seals' differentiation. This is clearly illustrated by the fair trade organisations' different strategies: as WTFO emphasises integrated delivery chains and quality, FLO seal is focusing on product certification and quantity.

'Charity is justice swamped in the dunghole of mercy'

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi

While fighting for markets, companies appeal to the consumers' conscience. Slogans like 'the power of consumers' suggest a potential for the change of markets by making conscious individual shopping decisions – true to the motto: a fair, beautiful world is for sale. This kind of fair trade marketing works as concealment of the fundamental relations of globalised capitalism.

Additionally, in turn it appears ethically reprehensible being too poor to afford labelled products and poorer consumers have to decide to which producers they can afford to grant 'fair' wages. Therefore, the choice between wealth and poverty is exclusively based on their purchase decision.

In our opinion, this is unsustainable and also ultimately inadequate as consumers and social-political local context are concerned. Instead, regulations and global change need to be established which are not focusing on individual responsibility for historical exploitative structures but on an entirely different whole and absolutely different conditions.

In the absence of radical political demands, fair trade will transform into a socially acceptable justification instrument of post-colonial trade relations and will contribute to these conditions' perpetuation instead of overcoming them as a perspective and challenge of society.

Café Libertad Kollektiv as a player in solidary trade puts special emphasis on cooperation with cooperatives embedded in their home countries' social movements and exercising an explicitly political self-conception.

An essential part of our self-conception aiming at a change of society as a whole and an economy based on solidarity are our own political activities as well as financial support of emancipatory initiatives and anti-capitalist movements via sponsoring and annual price negotiations on an equal footing.

[1] https://utopia.de/0/ratgeber/welchem-guetesiegel-vertrauen-biosiegel-eg-oekoverordnung-label (27.1.2018). 'A particular subgroup being seals protected by copyright and competition law' (ibid.)

[2] Ökotest Nr. 8 / August 2012: „Fairer Handel und Unfaire Geschäfte“, p. 24

[3] ibid. p. 20

[4] ibid.

[5] Comprehensive criticism of labels and seals see Kathrin Hartmann (2009): „Ende der Märchenstunde“

[6] https://www.forum-fairer-handel.de/fairer-handel/definition/ (28.01.2018)

[7] https://www.oeku-buero.de/info-blatt-50/articles/erfahrungen-der-kaffeekampagne-el-salvador.html (10.02.2018)

[8] See 'price fluctuations'

[9] Hornung et al: Wo Kritik war, ist Konsum. Das Problem mit Fair Trade. In: Kurswechsel 1/2011: pp. 126-130, p. 126-7.

[10] https://www.fairtrade-deutschland.de/service/presse/details/12-milliarden-umsatz-mit-fairtrade-produkten-1951.html (27.01.2018)

[11] Forum Fairer Handel e.V. (2017): Aktuelle Entwicklungen im Fairen Handel, p. 4: https://www.faire-woche.de/fileadmin/user_upload/media/fairer_handel/zahlen_fakten/2017-07-20_aktuelle_entwicklungen_im_fh_2017.pdf (31.01.2018)

[12] ibid., p. 127

[13] All info: https://wfto.com/about-us/about-wfto (27.01.2018) and Forum Fairer Handel e.V. (2015): „Monitoring und Zertifizierung im Fairen Handel“

[14] ibid.

[15] As this is not certification based on legal regulation, the WTFO symbol is called a label.

[16] http://www.forum-fairer-handel.de/de/rss-feed/rss/artikel/article/fair-nach-innen-und-aussen/ (27.01.2018)

[17] Forum Fairer Handel e.V. (2015): „Monitoring und Zertifizierung im Fairen Handel“, p. 14.

[18] In external communication, the association is calling itself 'Fairtrade International' but has been established using „Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International“ (FLO).

[19] https://www.fairtrade.net/about-fairtrade/fairtrade-system.html (28.01.2018).

[20] Forum Fairer Handel e.V. (2015): „Monitoring und Zertifizierung im Fairen Handel“, p. 10.

[21] https://www.fairtrade-deutschland.de/was-ist-fairtrade/fairtrade-standards.html (28.01.2018)

[22] https://www.fairtrade.net/standards/price-and-premium-info.html (11.02.2018)

[23] Forum Fairer Handel e.V. (2015): „Monitoring und Zertifizierung im Fairen Handel“, p. 10.

[24] http://www.fairtrade.de/cms/media/pdf/FAIRTRADE-Zertifizierungssystem_im_Detail.pdf (28.01.2018)

[25] https://www.flocert.net/solutions/fairtrade-resources/cost-calculator/ (14.01.2018).You can calculate any constellation using the FLOCERT calculator.

[26] Among others Christopher Cramer: The Fair Trade, Employment and Poverty Reduction (FTEPR) http://ftepr.org/ (14.01.2018) or Benjamin Hornung, Andreas Meyerhöfer, Matthias Elsas: Wo Kritik war, ist Konsum. Das Problem mit Fair Trade. In: Kurswechsel 1/2011: pp. 126-130. See also ORF Weltjournal-Doku (2012): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-514XPSLz58 (31.01.2018)

[27] Zeit Online: Das Geschäft mit dem schlechten Geschmack (2015). http://www.zeit.de/wirtschaft/2015-01/fairtrade-qualitaet (31.01.2018)

[28] Comment on Fairtrade Award 2012: http://www.ewnw.de/sites/default/files/2012%20PM%20Transfair%20Awards%20Lidl.pdf (31.01.2018)

[29] We are not the only ones criticising this: For instance, Eine Welt Netzwerk Hamburg e.V. has expressed outrage regarding this type of award policy http://www.ewnw.de/fairtrade-award-lidl-ist-geschmacklos (31.01.2018)

[30] Comprehensive criticism of labels and seals see Kathrin Hartmann (2009): „Ende der Märchenstunde“

[31] https://www.fairtrade-deutschland.de/faq.html#c5155 (01.02.2018)

[32] https://utopia.de/siegel/fairtrade-siegel-bedeutung-kritik/ (01.02.2018)

[33] Forum Fairer Handel (2011): „Wesentliche Änderungen in den Fairtrade-Standards 2010/2011, https://www.forum-fairer-handel.de/fileadmin/user_upload/dateien/publikationen/materialien_des_ffh/wesentliche_aenderungen_in_den_fairtrade_standards_2010-11.pdf (01.02.2018)

[34] ibid.

[35] https://www.fairtrade.net/fileadmin/user_upload/content/2009/resources/2013-14_AnnualReport_FairtradeIntl_web.pdf , p. 18 (11.02.2018)

[36] http://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/unternehmen/fairer-handel-ist-ein-milliardenmarkt-geworden-13794971.html (11.02.2018)

[37] See Wegener & Becker (2010): „Rundum gut? Überblick und Bewertung der Zertifizierung von Sozialstandards, fairen Handelspraktiken und Regionalität im Biohandel und im fairen Handel.“ Ed.: KATE e.V. and Copine eG